Nature's conveyor beltGlaciers are very effective agents in transporting large volume of debris. Best observed is debris carried on the top of the glacier (supraglacial debris), but large amounts are also carried at the bed (basal debis). In the following images, debris can be seen in both situations, and also illustrates the effect it has on the ice surface. |

Large amounts of debris are transported by Breithorngletscher (right) and Schwarzgletscher (centre) flowing off Breithorn (4164 m) near Zermatt, Switzerland. Note how lateral moraines become medial moraines where glaciers flow together. JA |  Supraglacial (or surface) debris is normally the result of rock falls, but occasionally larger landslides occur, as in the accumulation area of Glacier Pré du Bar in the Mont Blanc area, French Alps (11. Aug. 1982). JA |  The parallel ‘tramlines’ on the Grosser Aletschgletscher, Berner Oberland, Switzerland, are medial moraines, each formed where two ice streams combine. The three peaks in the background, from left to right, are Jungfrau (4158 m), Mönch (4099 m) and Eiger (3970 m). MH |  Where the ice slows down and becomes crevassed, medial moraines merge into one another, as on Hubbard Glacier, Alaska. Despite now merging into a continuous cover of debris, the individual moraines may be distinguished on the basis of the different-coloured rock types. MH |

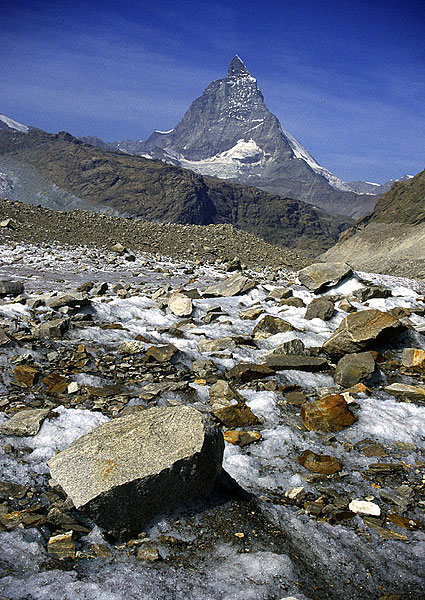

Supraglacial debris may be more evenly scattered over the glacier surface if rockfalls are intermittent. This shows a view down the Gornergletscher, looking towards the Matterhorn (4477 m). MH |  Isolated blocks on the glacier surface often protect the ice from melting, especially when solar radiation is strong, forming glacier tables. This example is on Vadret Pers, southeastern Switzerland, with Piz Palü (3905 m) in the background. JA |  Supraglacial streams often wash out the finer material (sand and pebbles) from the moraine cover. Pockets of debris protect the ice from ablation, and dirt cones may form, as here on Glacier de Tsijiore Nouve, below Pigne d’Arolla (3796 m), Switzerland. MH |  The tongue of Chola Glacier in the Khumbu Himal of Nepal is completely debris-mantled. The steep flanks of the glacier are bounded by lateral moraines which merge imperceptibly into glacier ice beneath the debris cover. MH |

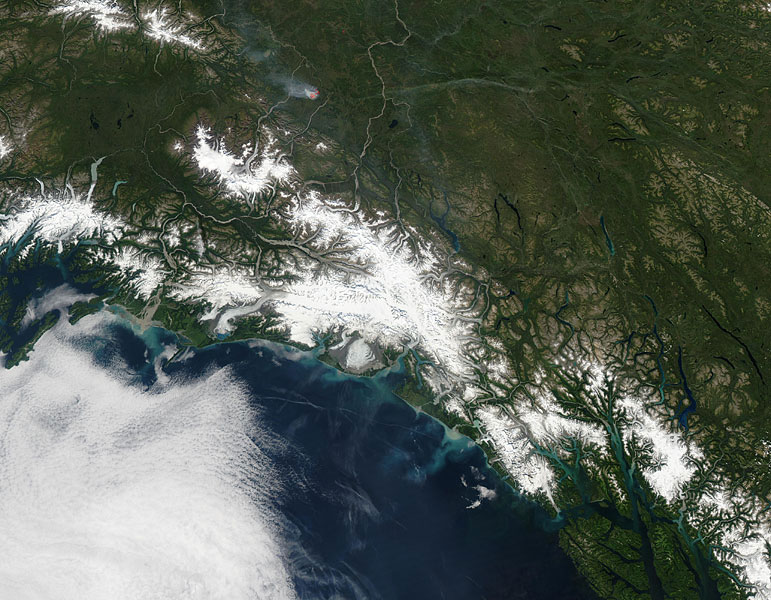

Many glaciers in high mountain regions are completely mantled by debris in their lower reaches. This view shows the uneven surface of loose debris and supraglacial ponds on the surface of Khumbu Glacier, Nepal. The peak of Pumori is in the background. MH |  Much debris is transported within the body of the glacier ‘englacially’. It can gain this position by deformation processes lifting it from the bed or from the surface by falling into crevasses. In this case, Taylor Glacier in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica, debris has frozen to the bed as a series of layers. Debris melting out from beneath the debris-rich ice is ‘till’. MH |  Satellite image of the Chugach Mountains (far left) and the St Elias Mountains (centre and right) with extensive icefields. Glaciers deliver large volumes of suspended matter, seen as light coloured plumes, to the coast. Photo courtesy of NASA, image taken 22 August 2003. |  Kronebreen in NW Spitsbergen produces large numbers of icebergs. Many are rich in basal glacial debris, and float across the waters of Kongsfjorden, slowly releasing their load onto the sea bed as dropstones. The dark brown iceberg dwarfs the person standing on the shore beyond. MH |